並行性

はじめに

The definitive reference on concurrency and parallelism in Haskell is Simon Marlow's text. This will section will just gloss over these topics because they are far better explained in this book.

See: Parallel and Concurrent Programming in Haskell

forkIO :: IO () -> IO ThreadId

Haskell threads are extremely cheap to spawn, using only 1.5KB of RAM depending on the platform and are much cheaper than a pthread in C. Calling forkIO 106 times completes just short of a 1s. Additionally, functional purity in Haskell also guarantees that a thread can almost always be terminated even in the middle of a computation without concern.

See: The Scheduler

スパーク

The most basic "atom" of parallelism in Haskell is a spark. It is a hint to the GHC runtime that a computation can be evaluated to weak head normal form in parallel.

rpar :: a -> Eval a

rseq :: Strategy a

rdeepseq :: NFData a => Strategy a

runEval :: Eval a -> a

rpar a spins off a separate spark that evolutes a to weak head normal form

and places the computation in the spark pool. When the runtime determines that

there is an available CPU to evaluate the computation it will evaluate (

convert ) the spark. If the main thread of the main thread of the program is

the evaluator for the spark, the spark is said to have fizzled. Fizzling is

generally bad and indicates that the logic or parallelism strategy is not well

suited to the work that is being evaluated.

The spark pool is also limited ( but user-adjustable ) to a default of 8000 (as of GHC 7.8.3 ). Sparks that are created beyond that limit are said to overflow.

-- Evaluates the arguments to f in parallel before application.

par2 f x y = x `rpar` y `rpar` f x y

An argument to rseq forces the evaluation of a spark before evaluation

continues.

Action Description

Fizzled The resulting value has already been evaluated by the main thread so the spark need not be converted.

Dud The expression has already been evaluated, the computed value is returned and the spark is not converted.

GC'd The spark is added to the spark pool but the result is not referenced, so it is garbage collected.

Overflowed Insufficient space in the spark pool when spawning.

The parallel runtime is necessary to use sparks, and the resulting program must

be compiled with -threaded. Additionally the program itself can be specified

to take runtime options with -rtsopts such as the number of cores to use.

ghc -threaded -rtsopts program.hs

./program +RTS -s N8 -- use 8 cores

The runtime can be asked to dump information about the spark evaluation by

passing the -s flag.

$ ./spark +RTS -N4 -s

Tot time (elapsed) Avg pause Max pause

Gen 0 5 colls, 5 par 0.02s 0.01s 0.0017s 0.0048s

Gen 1 3 colls, 2 par 0.00s 0.00s 0.0004s 0.0007s

Parallel GC work balance: 1.83% (serial 0%, perfect 100%)

TASKS: 6 (1 bound, 5 peak workers (5 total), using -N4)

SPARKS: 20000 (20000 converted, 0 overflowed, 0 dud, 0 GC'd, 0 fizzled)

The parallel computations themselves are sequenced in the Eval monad, whose

evaluation with runEval is itself a pure computation.

example :: (a -> b) -> a -> a -> (b, b)

example f x y = runEval $ do

a <- rpar $ f x

b <- rpar $ f y

rseq a

rseq b

return (a, b)

スレッドスコープ

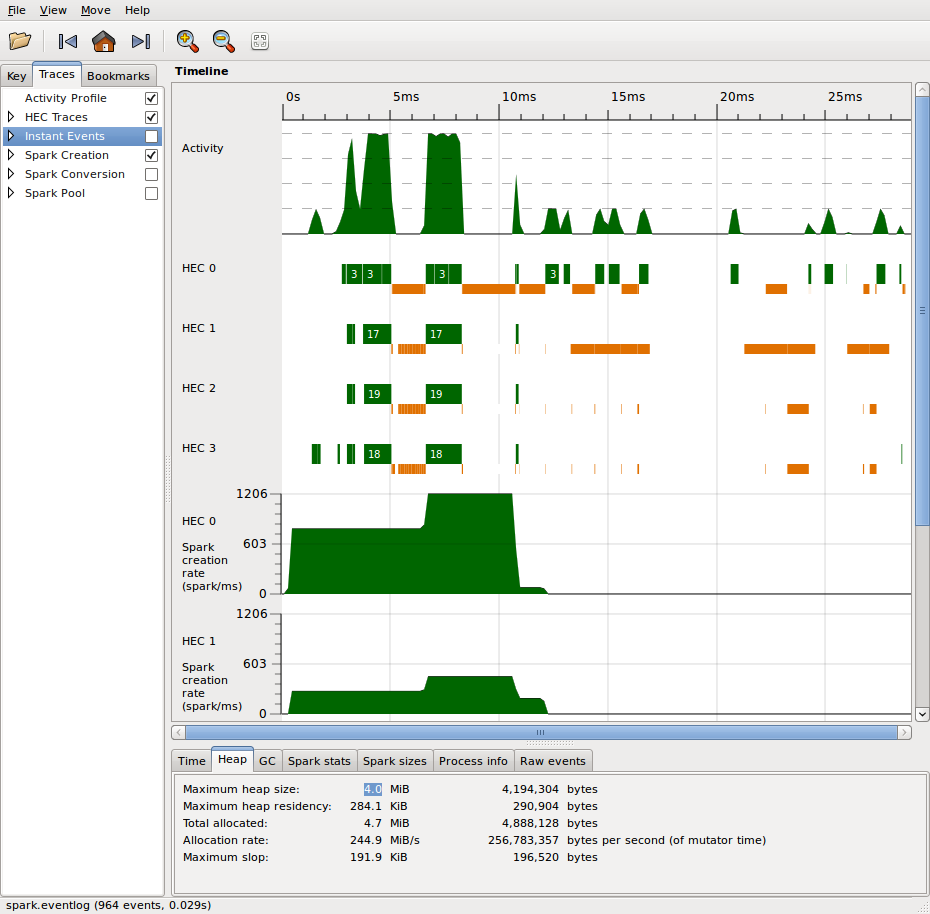

Passing the flag -l generates the eventlog which can be rendered with the

threadscope library.

$ ghc -O2 -threaded -rtsopts -eventlog Example.hs

$ ./program +RTS -N4 -l

$ threadscope Example.eventlog

See Simon Marlows's Parallel and Concurrent Programming in Haskell for a detailed guide on interpreting and profiling using Threadscope.

See:

戦略

type Strategy a = a -> Eval a

using :: a -> Strategy a -> a

Sparks themselves form the foundation for higher level parallelism constructs known as strategies which

adapt spark creation to fit the computation or data structure being evaluated. For instance if we wanted to

evaluate both elements of a tuple in parallel we can create a strategy which uses sparks to evaluate both

sides of the tuple.

import Control.Parallel.Strategies

parPair' :: Strategy (a, b)

parPair' (a, b) = do

a' <- rpar a

b' <- rpar b

return (a', b')

fib :: Int -> Int

fib 0 = 0

fib 1 = 1

fib n = fib (n-1) + fib (n-2)

serial :: (Int, Int)

serial = (fib 30, fib 31)

parallel :: (Int, Int)

parallel = runEval . parPair' $ (fib 30, fib 31)

This pattern occurs so frequently the combinator using can be used to write it equivelantly in

operator-like form that may be more visually appealing to some.

using :: a -> Strategy a -> a

x `using` s = runEval (s x)

parallel ::: (Int, Int)

parallel = (fib 30, fib 31) `using` parPair

For a less contrived example consider a parallel parmap which maps a pure function over a list of a values

in parallel.

import Control.Parallel.Strategies

parMap' :: (a -> b) -> [a] -> Eval [b]

parMap' f [] = return []

parMap' f (a:as) = do

b <- rpar (f a)

bs <- parMap' f as

return (b:bs)

result :: [Int]

result = runEval $ parMap' (+1) [1..1000]

The functions above are quite useful, but will break down if evaluation of the arguments needs to be

parallelized beyond simply weak head normal form. For instance if the arguments to rpar is a nested

constructor we'd like to parallelize the entire section of work in evaluated the expression to normal form

instead of just the outer layer. As such we'd like to generalize our strategies so the the evaluation strategy

for the arguments can be passed as an argument to the strategy.

Control.Parallel.Strategies contains a generalized version of rpar which embeds additional evaluation

logic inside the rpar computation in Eval monad.

rparWith :: Strategy a -> Strategy a

Using the deepseq library we can now construct a Strategy variant of rseq that evaluates to full normal form.

rdeepseq :: NFData a => Strategy a

rdeepseq x = rseq (force x)

We now can create a "higher order" strategy that takes two strategies and itself yields a a computation which when evaluated uses the passed strategies in it's scheduling.

import Control.DeepSeq

import Control.Parallel.Strategies

evalPair :: Strategy a -> Strategy b -> Strategy (a, b)

evalPair sa sb (a, b) = do

a' <- sa a

b' <- sb b

return (a', b')

parPair :: Strategy a -> Strategy b -> Strategy (a, b)

parPair sa sb = evalPair (rparWith sa) (rparWith sb)

fib :: Int -> Int

fib 0 = 0

fib 1 = 1

fib n = fib (n-1) + fib (n-2)

serial :: ([Int], [Int])

serial = (a, b)

where

a = fmap fib [0..30]

b = fmap fib [1..30]

parallel :: ([Int], [Int])

parallel = (a, b) `using` evalPair rdeepseq rdeepseq

where

a = fmap fib [0..30]

b = fmap fib [1..30]

These patterns are implemented in the Strategies library along with several other general forms and combinators for combining strategies to fit many different parallel computations.

parTraverse :: Traversable t => Strategy a -> Strategy (t a)

dot :: Strategy a -> Strategy a -> Strategy a

($||) :: (a -> b) -> Strategy a -> a -> b

(.||) :: (b -> c) -> Strategy b -> (a -> b) -> a -> c

See:

STM

atomically :: STM a -> IO a

orElse :: STM a -> STM a -> STM a

retry :: STM a

newTVar :: a -> STM (TVar a)

newTVarIO :: a -> IO (TVar a)

writeTVar :: TVar a -> a -> STM ()

readTVar :: TVar a -> STM a

modifyTVar :: TVar a -> (a -> a) -> STM ()

modifyTVar' :: TVar a -> (a -> a) -> STM ()

Software Transactional Memory is a technique for guaranteeing atomicity of values in parallel computations, such that all contexts view the same data when read and writes are guaranteed never to result in inconsistent states.

The strength of Haskell's purity guarantees that transactions within STM are pure and can always be rolled back if a commit fails.

import Control.Monad

import Control.Concurrent

import Control.Concurrent.STM

type Account = TVar Double

transfer :: Account -> Account -> Double -> STM ()

transfer from to amount = do

available <- readTVar from

when (amount > available) retry

modifyTVar from (+ (-amount))

modifyTVar to (+ amount)

-- Threads are scheduled non-deterministically.

actions :: Account -> Account -> [IO ThreadId]

actions a b = map forkIO [

-- transfer to

atomically (transfer a b 10)

, atomically (transfer a b (-20))

, atomically (transfer a b 30)

-- transfer back

, atomically (transfer a b (-30))

, atomically (transfer a b 20)

, atomically (transfer a b (-10))

]

main :: IO ()

main = do

accountA <- atomically $ newTVar 60

accountB <- atomically $ newTVar 0

sequence_ (actions accountA accountB)

balanceA <- atomically $ readTVar accountA

balanceB <- atomically $ readTVar accountB

print $ balanceA == 60

print $ balanceB == 0

Monad Par

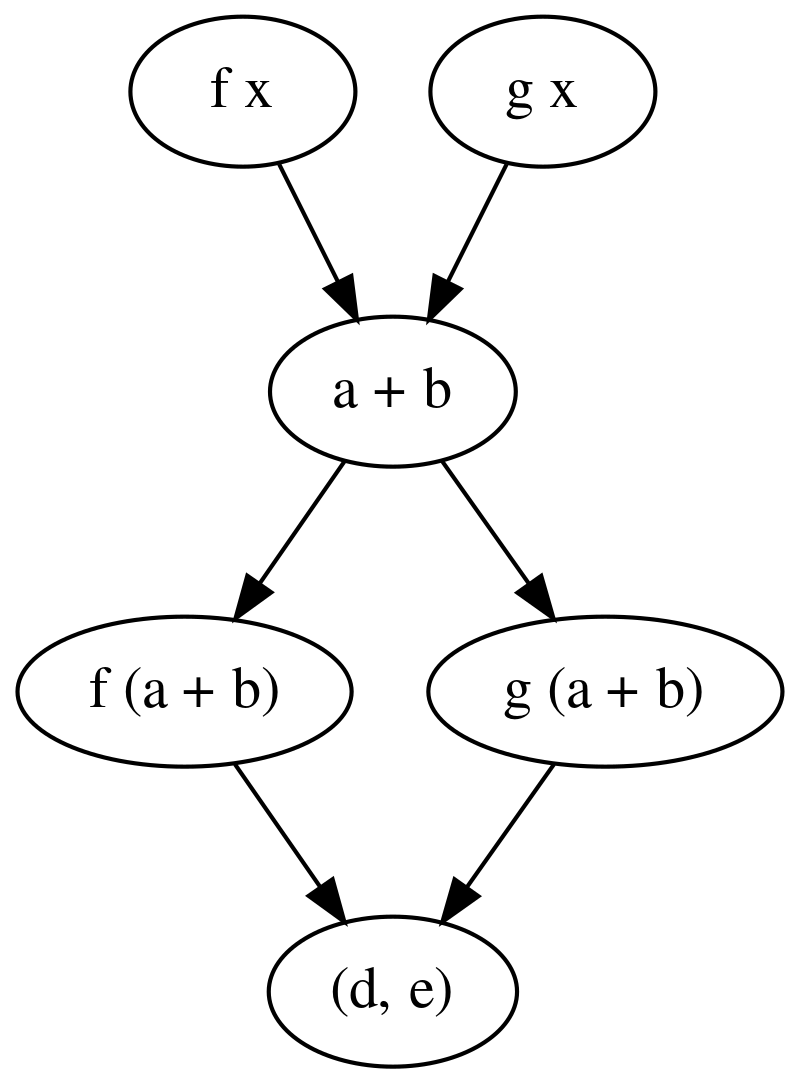

Using the Par monad we express our computation as a data flow graph which is

scheduled in order of the connections between forked computations which exchange

resulting computations with IVar.

new :: Par (IVar a)

put :: NFData a => IVar a -> a -> Par ()

get :: IVar a -> Par a

fork :: Par () -> Par ()

spawn :: NFData a => Par a -> Par (IVar a)

import Control.Monad

import Control.Monad.Par

f, g :: Int -> Int

f x = x + 10

g x = x * 10

-- f x g x

-- \ /

-- a + b

-- / \

-- f (a+b) g (a+b)

-- \ /

-- (d,e)

example1 :: Int -> (Int, Int)

example1 x = runPar $ do

[a,b,c,d,e] <- replicateM 5 new

fork (put a (f x))

fork (put b (g x))

a' <- get a

b' <- get b

fork (put c (a' + b'))

c' <- get c

fork (put d (f c'))

fork (put e (g c'))

d' <- get d

e' <- get e

return (d', e')

example2 :: [Int]

example2 = runPar $ do

xs <- parMap (+1) [1..25]

return xs

-- foldr (+) 0 (map (^2) [1..xs])

example3 :: Int -> Int

example3 n = runPar $ do

let range = (InclusiveRange 1 n)

let mapper x = return (x^2)

let reducer x y = return (x+y)

parMapReduceRangeThresh 10 range mapper reducer 0

async

Async is a higher level set of functions that work on top of Control.Concurrent and STM.

async :: IO a -> IO (Async a)

wait :: Async a -> IO a

cancel :: Async a -> IO ()

concurrently :: IO a -> IO b -> IO (a, b)

race :: IO a -> IO b -> IO (Either a b)

import Control.Monad

import Control.Applicative

import Control.Concurrent

import Control.Concurrent.Async

import Data.Time

timeit :: IO a -> IO (a,Double)

timeit io = do

t0 <- getCurrentTime

a <- io

t1 <- getCurrentTime

return (a, realToFrac (t1 `diffUTCTime` t0))

worker :: Int -> IO Int

worker n = do

-- simulate some work

threadDelay (10^2 * n)

return (n * n)

-- Spawn 2 threads in parallel, halt on both finished.

test1 :: IO (Int, Int)

test1 = do

val1 <- async $ worker 1000

val2 <- async $ worker 2000

(,) <$> wait val1 <*> wait val2

-- Spawn 2 threads in parallel, halt on first finished.

test2 :: IO (Either Int Int)

test2 = do

let val1 = worker 1000

let val2 = worker 2000

race val1 val2

-- Spawn 10000 threads in parallel, halt on all finished.

test3 :: IO [Int]

test3 = mapConcurrently worker [0..10000]

main :: IO ()

main = do

print =<< timeit test1

print =<< timeit test2

print =<< timeit test3