GHC

ブロック図

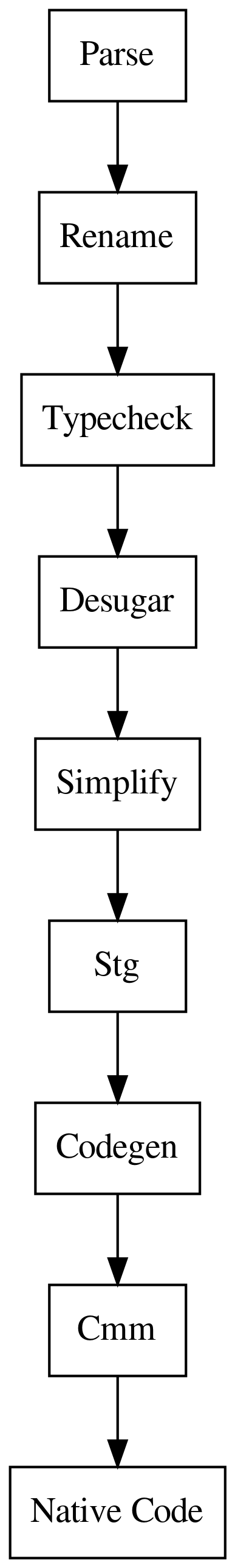

The flow of code through GHC is a process of translation between several

intermediate languages and optimizations and transformations thereof. A common

pattern for many of these AST types is they are parametrised over a binder type

and at various stages the binders will be transformed, for example the Renamer

pass effectively translates the HsSyn datatype from a AST parametrized over

literal strings as the user enters into a HsSyn parameterized over qualified

names that includes modules and package names into a higher level Name type.

- Parser/Frontend: An enormous AST translated from human syntax that makes explicit possible all expressible syntax ( declarations, do-notation, where clauses, syntax extensions, template haskell, ... ). This is unfiltered Haskell and it is enormous.

- Renamer takes syntax from the frontend and transforms all names to be

qualified (

base:Prelude.mapinstead ofmap) and any shadowed names in lambda binders transformed into unique names. - Typechecker is a large pass that serves two purposes, first is the core type

bidirectional inference engine where most of the work happens and the

translation between the frontend

Coresyntax. - Desugarer translates several higher level syntactic constructors

wherestatements are turned into (possibly recursive) nestedletstatements.- Nested pattern matches are expanded out into splitting trees of case statements.

- do-notation is expanded into explicit bind statements.

- Lots of others.

- Simplifier transforms many Core constructs into forms that are more adaptable to compilation. For example let statements will be floated or raised, pattern matches will simplified, inner loops will be pulled out and transformed into more optimal forms. Non-intuitively the resulting may actually be much more complex (for humans) after going through the simplifier!

- Stg pass translates the resulting Core into STG (Spineless Tagless G-Machine) which effectively makes all laziness explicit and encodes the thunks and update frames that will be handled during evaluation.

- Codegen/Cmm pass will then translate STG into Cmm (flavoured C--) a simple imperative language that manifests the low-level implementation details of runtime types. The runtime closure types and stack frames are made explicit and low-level information about the data and code (arity, updatability, free variables, pointer layout) made manifest in the info tables present on most constructs.

- Native Code The final pass will than translate the resulting code into either LLVM or Assembly via either through GHC's home built native code generator (NCG) or the LLVM backend.

Information for about each pass can dumped out via a rather large collection of

flags. The GHC internals are very accessible although some passes are somewhat

easier to understand than others. Most of the time -ddump-simpl and

-ddump-stg are sufficient to get an understanding of how the code will

compile, unless of course you're dealing with very specialized optimizations or

hacking on GHC itself.

Flag Action

-ddump-parsed Frontend AST.

-ddump-rn Output of the rename pass.

-ddump-tc Output of the typechecker.

-ddump-splices Output of TemplateHaskell splices.

-ddump-types Typed AST representation.

-ddump-deriv Output of deriving instances.

-ddump-ds Output of the desugar pass.

-ddump-spec Output of specialisation pass.

-ddump-rules Output of applying rewrite rules.

-ddump-vect Output results of vectorize pass.

-ddump-simpl Ouptut of the SimplCore pass.

-ddump-inlinings Output of the inliner.

-ddump-cse Output of the common subexpression elimination pass.

-ddump-prep The CorePrep pass.

-ddump-stg The resulting STG.

-ddump-cmm The resulting Cmm.

-ddump-opt-cmm The resulting Cmm optimization pass.

-ddump-asm The final assembly generated.

-ddump-llvm The final LLVM IR generated.

コア

Core is the explicitly typed System-F family syntax through that all Haskell constructs can be expressed in.

To inspect the core from GHCi we can invoke it using the following flags and the following shell alias. We have explicitly disable the printing of certain metadata and longform names to make the representation easier to read.

alias ghci-core="ghci -ddump-simpl -dsuppress-idinfo \

-dsuppress-coercions -dsuppress-type-applications \

-dsuppress-uniques -dsuppress-module-prefixes"

At the interactive prompt we can then explore the core representation interactively:

$ ghci-core

λ: let f x = x + 2 ; f :: Int -> Int

==================== Simplified expression ====================

returnIO

(: ((\ (x :: Int) -> + $fNumInt x (I# 2)) `cast` ...) ([]))

λ: let f x = (x, x)

==================== Simplified expression ====================

returnIO (: ((\ (@ t) (x :: t) -> (x, x)) `cast` ...) ([]))

ghc-core is also very useful for looking at GHC's compilation artifacts.

$ ghc-core --no-cast --no-asm

Alternatively the major stages of the compiler ( parse tree, core, stg, cmm, asm ) can be manually outputted and inspected by passing several flags to the compiler:

$ ghc -ddump-to-file -ddump-parsed -ddump-simpl -ddump-stg -ddump-cmm -ddump-asm

Reading Core

Core from GHC is roughly human readable, but it's helpful to look at simple human written examples to get the hang of what's going on.

id :: a -> a

id x = x

id :: forall a. a -> a

id = \ (@ a) (x :: a) -> x

idInt :: GHC.Types.Int -> GHC.Types.Int

idInt = id @ GHC.Types.Int

compose :: (b -> c) -> (a -> b) -> a -> c

compose f g x = f (g x)

compose :: forall b c a. (b -> c) -> (a -> b) -> a -> c

compose = \ (@ b) (@ c) (@ a) (f1 :: b -> c) (g :: a -> b) (x1 :: a) -> f1 (g x1)

map :: (a -> b) -> [a] -> [b]

map f [] = []

map f (x:xs) = f x : map f xs

map :: forall a b. (a -> b) -> [a] -> [b]

map =

\ (@ a) (@ b) (f :: a -> b) (xs :: [a]) ->

case xs of _ {

[] -> [] @ b;

: y ys -> : @ b (f y) (map @ a @ b f ys)

}

Machine generated names are created for a lot of transformation of Core.

Generally they consist of a prefix and unique identifier. The prefix is often

pass specific ( i.e. ds for desugar generated name s) and sometimes specific

names are generated for specific automatically generated code. A non exhaustive

cheat sheet is given below for deciphering what a name is and what it might

stand for:

| Prefix | Description |

|---|---|

$f... |

Dict-fun identifiers (from inst decls) |

$dmop |

Default method for 'op' |

$wf |

Worker for function 'f' |

$sf |

Specialised version of f |

$gdm |

Generated class method |

$d |

Dictionary names |

$s |

Specialized function name |

$f |

Foreign export |

$pnC |

n'th superclass selector for class C |

T:C |

Tycon for dictionary for class C |

D:C |

Data constructor for dictionary for class C |

NTCo:T |

Coercion for newtype T to its underlying runtime representation |

Of important note is that the Λ and λ for type-level and value-level lambda

abstraction are represented by the same symbol (\) in core, which is a

simplifying detail of the GHC's implementation but a source of some confusion

when starting.

-- System-F Notation

Λ b c a. λ (f1 : b -> c) (g : a -> b) (x1 : a). f1 (g x1)

-- Haskell Core

\ (@ b) (@ c) (@ a) (f1 :: b -> c) (g :: a -> b) (x1 :: a) -> f1 (g x1)

The seq function has an intuitive implementation in the Core language.

x `seq` y

case x of _ {

__DEFAULT -> y

}

One particularly notable case of the Core desugaring process is that pattern matching on overloaded numbers

implicitly translates into equality test (i.e. Eq).

f 0 = 1

f 1 = 2

f 2 = 3

f 3 = 4

f 4 = 5

f _ = 0

f :: forall a b. (Eq a, Num a, Num b) => a -> b

f =

\ (@ a)

(@ b)

($dEq :: Eq a)

($dNum :: Num a)

($dNum1 :: Num b)

(ds :: a) ->

case == $dEq ds (fromInteger $dNum (__integer 0)) of _ {

False ->

case == $dEq ds (fromInteger $dNum (__integer 1)) of _ {

False ->

case == $dEq ds (fromInteger $dNum (__integer 2)) of _ {

False ->

case == $dEq ds (fromInteger $dNum (__integer 3)) of _ {

False ->

case == $dEq ds (fromInteger $dNum (__integer 4)) of _ {

False -> fromInteger $dNum1 (__integer 0);

True -> fromInteger $dNum1 (__integer 5)

};

True -> fromInteger $dNum1 (__integer 4)

};

True -> fromInteger $dNum1 (__integer 3)

};

True -> fromInteger $dNum1 (__integer 2)

};

True -> fromInteger $dNum1 (__integer 1)

}

Of course, adding a concrete type signature changes the desugar just matching on the unboxed values.

f :: Int -> Int

f =

\ (ds :: Int) ->

case ds of _ { I# ds1 ->

case ds1 of _ {

__DEFAULT -> I# 0;

0 -> I# 1;

1 -> I# 2;

2 -> I# 3;

3 -> I# 4;

4 -> I# 5

}

}

See:

インライナ

infixr 0 $

($):: (a -> b) -> a -> b

f $ x = f x

Having to enter a secondary closure every time we used ($) would introduce

an enormous overhead. Fortunately GHC has a pass to eliminate small functions

like this by simply replacing the function call with the body of it's definition

at appropriate call-sites. There compiler contains a variety heuristics for

determining when this kind of substitution is appropriate and the potential

costs involved.

In addition to the automatic inliner, manual pragmas are provided for more granular control over inlining. It's important to note that naive inlining quite often results in significantly worse performance and longer compilation times.

{-# INLINE func #-}

{-# INLINABLE func #-}

{-# NOINLINE func #-}

For example the contrived case where we apply a binary function to two arguments. The function body is small and instead of entering another closure just to apply the given function, we could in fact just inline the function application at the call site.

{-# INLINE foo #-}

{-# NOINLINE bar #-}

foo :: (a -> b -> c) -> a -> b -> c

foo f x y = f x y

bar :: (a -> b -> c) -> a -> b -> c

bar f x y = f x y

test1 :: Int

test1 = foo (+) 10 20

test2 :: Int

test2 = bar (+) 20 30

Looking at the core, we can see that in test2 the function has indeed been

expanded at the call site and simply performs the addition there instead of

another indirection.

test1 :: Int

test1 =

let {

f :: Int -> Int -> Int

f = + $fNumInt } in

let {

x :: Int

x = I# 10 } in

let {

y :: Int

y = I# 20 } in

f x y

test2 :: Int

test2 = bar (+ $fNumInt) (I# 20) (I# 30)

Cases marked with NOINLINE generally indicate that the logic in the function

is using something like unsafePerformIO or some other unholy function. In

these cases naive inlining might duplicate effects at multiple call-sites

throughout the program which would be undesirable.

See:

辞書

The Haskell language defines the notion of Typeclasses but is agnostic to how they are implemented in a Haskell compiler. GHC's particular implementation uses a pass called the dictionary passing translation part of the elaboration phase of the typechecker which translates Core functions with typeclass constraints into implicit parameters of which record-like structures containing the function implementations are passed.

class Num a where

(+) :: a -> a -> a

(*) :: a -> a -> a

negate :: a -> a

This class can be thought as the implementation equivalent to the following parameterized record of functions.

data DNum a = DNum (a -> a -> a) (a -> a -> a) (a -> a)

add (DNum a m n) = a

mul (DNum a m n) = m

neg (DNum a m n) = n

numDInt :: DNum Int

numDInt = DNum plusInt timesInt negateInt

numDFloat :: DNum Float

numDFloat = DNum plusFloat timesFloat negateFloat

+ :: forall a. Num a => a -> a -> a

+ = \ (@ a) (tpl :: Num a) ->

case tpl of _ { D:Num tpl _ _ -> tpl }

* :: forall a. Num a => a -> a -> a

* = \ (@ a) (tpl :: Num a) ->

case tpl of _ { D:Num _ tpl _ -> tpl }

negate :: forall a. Num a => a -> a

negate = \ (@ a) (tpl :: Num a) ->

case tpl of _ { D:Num _ _ tpl -> tpl }

Num and Ord have simple translation but for monads with existential type

variables in their signatures, the only way to represent the equivalent

dictionary is using RankNTypes. In addition a typeclass may also include

superclasses which would be included in the typeclass dictionary and

parameterized over the same arguments and an implicit superclass constructor

function is created to pull out functions from the superclass for the current

monad.

data DMonad m = DMonad

{ bind :: forall a b. m a -> (a -> m b) -> m b

, return :: forall a. a -> m a

}

class (Functor t, Foldable t) => Traversable t where

traverse :: Applicative f => (a -> f b) -> t a -> f (t b)

traverse f = sequenceA . fmap f

data DTraversable t = DTraversable

{ dFunctorTraversable :: DFunctor t -- superclass dictionary

, dFoldableTraversable :: DFoldable t -- superclass dictionary

, traverse :: forall a. Applicative f => (a -> f b) -> t a -> f (t b)

}

Indeed this is not that far from how GHC actually implements typeclasses. It elaborates into projection functions and data constructors nearly identical to this, and are implicitly threaded for every overloaded identifier.

特殊化

Overloading in Haskell is normally not entirely free by default, although with an optimization called specialization it can be made to have zero cost at specific points in the code where performance is crucial. This is not enabled by default by virtue of the fact that GHC is not a whole-program optimizing compiler and most optimizations ( not all ) stop at module boundaries.

GHC's method of implementing typeclasses means that explicit dictionaries are threaded around implicitly throughout the call sites. This is normally the most natural way to implement this functionality since it preserves separate compilation. A function can be compiled independently of where it is declared, not recompiled at every point in the program where it's called. The dictionary passing allows the caller to thread the implementation logic for the types to the call-site where it can then be used throughout the body of the function.

Of course this means that in order to get at a specific typeclass function we need to project ( possibly multiple times ) into the dictionary structure to pluck out the function reference. The runtime makes this very cheap but not entirely free.

Many C++ compilers or whole program optimizing compilers do the opposite however, they explicitly specialize each and every function at the call site replacing the overloaded function with it's type-specific implementation. We can selectively enable this kind of behavior using class specialization.

module Specialize (spec, nonspec, f) where

{-# SPECIALIZE INLINE f :: Double -> Double -> Double #-}

f :: Floating a => a -> a -> a

f x y = exp (x + y) * exp (x + y)

nonspec :: Float

nonspec = f (10 :: Float) (20 :: Float)

spec :: Double

spec = f (10 :: Double) (20 :: Double)

Non-specialized

f :: forall a. Floating a => a -> a -> a

f =

\ (@ a) ($dFloating :: Floating a) (eta :: a) (eta1 :: a) ->

let {

a :: Fractional a

a = $p1Floating @ a $dFloating } in

let {

$dNum :: Num a

$dNum = $p1Fractional @ a a } in

* @ a

$dNum

(exp @ a $dFloating (+ @ a $dNum eta eta1))

(exp @ a $dFloating (+ @ a $dNum eta eta1))

In the specialized version the typeclass operations placed directly at the call site and are simply unboxed arithmetic. This will map to a tight set of sequential CPU instructions and is very likely the same code generated by C.

spec :: Double

spec = D# (*## (expDouble# 30.0) (expDouble# 30.0))

The non-specialized version has to project into the typeclass dictionary

($fFloatingFloat) 6 times and likely go through around 25 branches to

perform the same operation.

nonspec :: Float

nonspec =

f @ Float $fFloatingFloat (F# (__float 10.0)) (F# (__float 20.0))

For a tight loop over numeric types specializing at the call site can result in orders of magnitude performance increase. Although the cost in compile-time can often be non-trivial and when used function used at many call-sites this can slow GHC's simplifier pass to a crawl.

The best advice is profile and look for large uses of dictionary projection in tight loops and then specialize and inline in these places.

Using the SPECIALISE INLINE pragma can unintentionally cause GHC to diverge

if applied over a recursive function, it will try to specialize itself

infinitely.

静的コンパイル

On Linux, Haskell programs can be compiled into a standalone statically linked binary that includes the runtime statically linked into it.

$ ghc -O2 --make -static -optc-static -optl-static -optl-pthread Example.hs

$ file Example

Example: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (GNU/Linux), statically linked, for GNU/Linux 2.6.32, not stripped

$ ldd Example

not a dynamic executable

In addition the file size of the resulting binary can be reduced by stripping unneeded symbols.

$ strip Example

非ボックス型

The usual numerics types in Haskell can be considered to be a regular algebraic datatype with special constructor arguments for their underlying unboxed values. Normally unboxed types and explicit unboxing are not used in normal code, they are an implementation detail of the compiler and many optimizations exist to do the unboxing in a way that is guaranteed to be safe and preserve the high level semantics of Haskell. Nevertheless it is somewhat enlightening to understand how the types are implemented.

data Int = I# Int#

data Integer

= S# Int# -- Small integers

| J# Int# ByteArray# -- Large GMP integers

data Float = F# Float#

λ: :set -XMagicHash

λ: :m +GHC.Types

λ: :m +GHC.Prim

λ: :type 3#

3# :: GHC.Prim.Int#

λ: :type 3##

3## :: GHC.Prim.Word#

λ: :type 3.14#

3.14# :: GHC.Prim.Float#

λ: :type 3.14##

3.14## :: GHC.Prim.Double#

λ: :type 'c'#

'c'# :: GHC.Prim.Char#

λ: :type "Haskell"#

"Haskell"# :: Addr#

λ: :i Int

data Int = I# Int# -- Defined in GHC.Types

λ: :k Int#

Int# :: #

An unboxed type with kind # and will never unify a type variable of kind

*. Intuitively a type with kind * indicates a type with a uniform

runtime representation that can be used polymorphically.

- Lifted - Can contain a bottom term, represented by a pointer. (

Int,Any,(,)) - Unlited - Cannot contain a bottom term, represented by a value on the stack. (

Int#,(#, #))

{-# LANGUAGE BangPatterns, MagicHash, UnboxedTuples #-}

import GHC.Exts

import GHC.Prim

ex1 :: Bool

ex1 = gtChar# a# b#

where

!(C# a#) = 'a'

!(C# b#) = 'b'

ex2 :: Int

ex2 = I# (a# +# b#)

where

!(I# a#) = 1

!(I# b#) = 2

ex3 :: Int

ex3 = (I# (1# +# 2# *# 3# +# 4#))

ex4 :: (Int, Int)

ex4 = (I# (dataToTag# False), I# (dataToTag# True))

The function for integer arithmetic used in the Num typeclass for Int is

just pattern matching on this type to reveal the underlying unboxed value,

performing the builtin arithmetic and then performing the packing up into

Int again.

plusInt :: Int -> Int -> Int

(I# x) `plusInt` (I# y) = I# (x +# y)

Where (+#) is a low level function built into GHC that maps to intrinsic

integer addition instruction for the CPU.

plusInt :: Int -> Int -> Int

plusInt a b = case a of {

(I# a_) -> case b of {

(I# b_) -> I# (+# a_ b_);

};

};

Runtime values in Haskell are by default represented uniformly by a boxed

StgClosure* struct which itself contains several payload values, which can

themselves either be pointers to other boxed values or to unboxed literal values

that fit within the system word size and are stored directly within the closure

in memory. The layout of the box is described by a bitmap in the header for the

closure which describes which values in the payload are either pointers or

non-pointers.

The unpackClosure# primop can be used to extract this information at runtime

by reading off the bitmap on the closure.

{-# LANGUAGE MagicHash, UnboxedTuples #-}

{-# OPTIONS_GHC -O1 #-}

module Main where

import GHC.Exts

import GHC.Base

import Foreign

data Size = Size

{ ptrs :: Int

, nptrs :: Int

, size :: Int

} deriving (Show)

unsafeSizeof :: a -> Size

unsafeSizeof a =

case unpackClosure# a of

(# x, ptrs, nptrs #) ->

let header = sizeOf (undefined :: Int)

ptr_c = I# (sizeofArray# ptrs)

nptr_c = I# (sizeofByteArray# nptrs) `div` sizeOf (undefined :: Word)

payload = I# (sizeofArray# ptrs +# sizeofByteArray# nptrs)

size = header + payload

in Size ptr_c nptr_c size

data A = A {-# UNPACK #-} !Int

data B = B Int

main :: IO ()

main = do

print (unsafeSizeof (A 42))

print (unsafeSizeof (B 42))

For example the datatype with the UNPACK pragma contains 1 non-pointer and 0

pointers.

data A = A {-# UNPACK #-} !Int

Size {ptrs = 0, nptrs = 1, size = 16}

While the default packed datatype contains 1 pointer and 0 non-pointers.

data B = B Int

Size {ptrs = 1, nptrs = 0, size = 9}

The closure representation for data constructors are also "tagged" at the

runtime with the tag of the specific constructor. This is however not a runtime

type tag since there is no way to recover the type from the tag as all

constructor simply use the sequence (0, 1, 2, ...). The tag is used to

discriminate cases in pattern matching. The builtin dataToTag# can be used

to pluck off the tag for an arbitrary datatype. This is used in some cases when

desugaring pattern matches.

dataToTag# :: a -> Int#

For example:

-- data Bool = False | True

-- False ~ 0

-- True ~ 1

a :: (Int, Int)

a = (I# (dataToTag# False), I# (dataToTag# True))

-- (0, 1)

-- data Ordering = LT | EQ | GT

-- LT ~ 0

-- EQ ~ 1

-- GT ~ 2

b :: (Int, Int, Int)

b = (I# (dataToTag# LT), I# (dataToTag# EQ), I# (dataToTag# GT))

-- (0, 1, 2)

-- data Either a b = Left a | Right b

-- Left ~ 0

-- Right ~ 1

c :: (Int, Int)

c = (I# (dataToTag# (Left 0)), I# (dataToTag# (Right 1)))

-- (0, 1)

String literals included in the source code are also translated into several

primop operations. The Addr# type in Haskell stands for a static contagious

buffer pre-allocated on the Haskell heap that can hold a char* sequence. The

operation unpackCString# can scan this buffer and fold it up into a list of

Chars from inside Haskell.

unpackCString# :: Addr# -> [Char]

This is done in the early frontend desugarer phase, where literals are

translated into Addr# inline instead of giant chain of Cons'd characters. So

our "Hello World" translates into the following Core:

-- print "Hello World"

print (unpackCString# "Hello World"#)

See:

IOとST

Both the IO and the ST monad have special state in the GHC runtime and share a

very similar implementation. Both ST a and IO a are passing around an

unboxed tuple of the form:

(# token, a #)

The RealWorld# token is "deeply magical" and doesn't actually expand into

any code when compiled, but simply threaded around through every bind of the IO

or ST monad and has several properties of being unique and not being able to be

duplicated to ensure sequential IO actions are actually sequential.

unsafePerformIO can thought of as the unique operation which discards the

world token and plucks the a out, and is as the name implies not normally

safe.

The PrimMonad abstracts over both these monads with an associated data

family for the world token or ST thread, and can be used to write operations

that generic over both ST and IO. This is used extensively inside of the vector

package to allow vector algorithms to be written generically either inside of IO

or ST.

{-# LANGUAGE MagicHash #-}

{-# LANGUAGE UnboxedTuples #-}

import GHC.IO ( IO(..) )

import GHC.Prim ( State#, RealWorld )

import GHC.Base ( realWorld# )

instance Monad IO where

m >> k = m >>= \ _ -> k

return = returnIO

(>>=) = bindIO

fail s = failIO s

returnIO :: a -> IO a

returnIO x = IO $ \ s -> (# s, x #)

bindIO :: IO a -> (a -> IO b) -> IO b

bindIO (IO m) k = IO $ \ s -> case m s of (# new_s, a #) -> unIO (k a) new_s

thenIO :: IO a -> IO b -> IO b

thenIO (IO m) k = IO $ \ s -> case m s of (# new_s, _ #) -> unIO k new_s

unIO :: IO a -> (State# RealWorld -> (# State# RealWorld, a #))

unIO (IO a) = a

{-# LANGUAGE MagicHash #-}

{-# LANGUAGE UnboxedTuples #-}

{-# LANGUAGE TypeFamilies #-}

import GHC.IO ( IO(..) )

import GHC.ST ( ST(..) )

import GHC.Prim ( State#, RealWorld )

import GHC.Base ( realWorld# )

class Monad m => PrimMonad m where

type PrimState m

primitive :: (State# (PrimState m) -> (# State# (PrimState m), a #)) -> m a

internal :: m a -> State# (PrimState m) -> (# State# (PrimState m), a #)

instance PrimMonad IO where

type PrimState IO = RealWorld

primitive = IO

internal (IO p) = p

instance PrimMonad (ST s) where

type PrimState (ST s) = s

primitive = ST

internal (ST p) = p

See:

ghc-heap-view

Through some dark runtime magic we can actually inspect the StgClosure

structures at runtime using various C and Cmm hacks to probe at the fields of

the structure's representation to the runtime. The library ghc-heap-view can

be used to introspect such things, although there is really no use for this kind

of thing in everyday code it is very helpful when studying the GHC internals to

be able to inspect the runtime implementation details and get at the raw bits

underlying all Haskell types.

{-# LANGUAGE MagicHash #-}

import GHC.Exts

import GHC.HeapView

import System.Mem

main :: IO ()

main = do

-- Constr

clo <- getClosureData $! ([1,2,3] :: [Int])

print clo

-- Thunk

let thunk = id (1+1)

clo <- getClosureData thunk

print clo

-- evaluate to WHNF

thunk `seq` return ()

-- Indirection

clo <- getClosureData thunk

print clo

-- force garbage collection

performGC

-- Value

clo <- getClosureData thunk

print clo

A constructor (in this for cons constructor of list type) is represented by a

CONSTR closure that holds two pointers to the head and the tail. The integer

in the head argument is a static reference to the pre-allocated number and we

see a single static reference in the SRT (static reference table).

ConsClosure {

info = StgInfoTable {

ptrs = 2,

nptrs = 0,

tipe = CONSTR_2_0,

srtlen = 1

},

ptrArgs = [0x000000000074aba8/1,0x00007fca10504260/2],

dataArgs = [],

pkg = "ghc-prim",

modl = "GHC.Types",

name = ":"

}

We can also observe the evaluation and update of a thunk in process ( id (1+1) ). The initial thunk is simply a thunk type with a pointer to the code

to evaluate it to a value.

ThunkClosure {

info = StgInfoTable {

ptrs = 0,

nptrs = 0,

tipe = THUNK,

srtlen = 9

},

ptrArgs = [],

dataArgs = []

}

When forced it is then evaluated and replaced with an Indirection closure which points at the computed value.

BlackholeClosure {

info = StgInfoTable {

ptrs = 1,

nptrs = 0,

tipe = BLACKHOLE,

srtlen = 0

},

indirectee = 0x00007fca10511e88/1

}

When the copying garbage collector passes over the indirection, it then simply

replaces the indirection with a reference to the actual computed value computed

by indirectee so that future access does need to chase a pointer through the

indirection pointer to get the result.

ConsClosure {

info = StgInfoTable {

ptrs = 0,

nptrs = 1,

tipe = CONSTR_0_1,

srtlen = 0

},

ptrArgs = [],

dataArgs = [2],

pkg = "integer-gmp",

modl = "GHC.Integer.Type",

name = "S#"

}

STG

After being compiled into Core, a program is translated into a very similar intermediate form known as STG ( Spineless Tagless G-Machine ) an abstract machine model that makes all laziness explicit. The spineless indicates that function applications in the language do not have a spine of applications of functions are collapsed into a sequence of arguments. Currying is still present in the semantics since arity information is stored and partially applied functions will evaluate differently than saturated functions.

-- Spine

f x y z = App (App (App f x) y) z

-- Spineless

f x y z = App f [x, y, z]

All let statements in STG bind a name to a lambda form. A lambda form with no arguments is a thunk, while a lambda-form with arguments indicates that a closure is to be allocated that captures the variables explicitly mentioned.

Thunks themselves are either reentrant (\r) or updatable (\u) indicating

that the thunk and either yields a value to the stack or is allocated on the

heap after the update frame is evaluated All subsequent entry's of the thunk

will yield the already-computed value without needing to redo the same work.

A lambda form also indicates the static reference table a collection of references to static heap allocated values referred to by the body of the function.

For example turning on -ddump-stg we can see the expansion of the following

compose function.

-- Frontend

compose f g = \x -> f (g x)

-- Core

compose :: forall t t1 t2. (t1 -> t) -> (t2 -> t1) -> t2 -> t

compose =

\ (@ t) (@ t1) (@ t2) (f :: t1 -> t) (g :: t2 -> t1) (x :: t2) ->

f (g x)

-- STG

compose :: forall t t1 t2. (t1 -> t) -> (t2 -> t1) -> t2 -> t =

\r [f g x] let { sat :: t1 = \u [] g x; } in f sat;

SRT(compose): []

For a more sophisticated example, let's trace the compilation of the factorial function.

-- Frontend

fac :: Int -> Int -> Int

fac a 0 = a

fac a n = fac (n*a) (n-1)

-- Core

Rec {

fac :: Int -> Int -> Int

fac =

\ (a :: Int) (ds :: Int) ->

case ds of wild { I# ds1 ->

case ds1 of _ {

__DEFAULT ->

fac (* @ Int $fNumInt wild a) (- @ Int $fNumInt wild (I# 1));

0 -> a

}

}

end Rec }

-- STG

fac :: Int -> Int -> Int =

\r srt:(0,*bitmap*) [a ds]

case ds of wild {

I# ds1 ->

case ds1 of _ {

__DEFAULT ->

let {

sat :: Int =

\u srt:(1,*bitmap*) []

let { sat :: Int = NO_CCS I#! [1]; } in - $fNumInt wild sat; } in

let { sat :: Int = \u srt:(1,*bitmap*) [] * $fNumInt wild a;

} in fac sat sat;

0 -> a;

};

};

SRT(fac): [fac, $fNumInt]

Notice that the factorial function allocates two thunks ( look for \u)

inside of the loop which are updated when computed. It also includes static

references to both itself (for recursion) and the dictionary for instance of

Num typeclass over the type Int.

ワーカとラッパ

With -O2 turned on GHC will perform a special optimization known as the

Worker-Wrapper transformation which will split the logic of the factorial

function across two definitions, the worker will operate over stack unboxed

allocated machine integers which compiles into a tight inner loop while the

wrapper calls into the worker and collects the end result of the loop and

packages it back up into a boxed heap value. This can often be an order of of

magnitude faster than the naive implementation which needs to pack and unpack

the boxed integers on every iteration.

-- Worker

$wfac :: Int# -> Int# -> Int# =

\r [ww ww1]

case ww1 of ds {

__DEFAULT ->

case -# [ds 1] of sat {

__DEFAULT ->

case *# [ds ww] of sat { __DEFAULT -> $wfac sat sat; };

};

0 -> ww;

};

SRT($wfac): []

-- Wrapper

fac :: Int -> Int -> Int =

\r [w w1]

case w of _ {

I# ww ->

case w1 of _ {

I# ww1 -> case $wfac ww ww1 of ww2 { __DEFAULT -> I# [ww2]; };

};

};

SRT(fac): []

See:

Zエンコーディング

The Z-encoding is Haskell's convention for generating names that are safely represented in the compiler target language. Simply put the z-encoding renames many symbolic characters into special sequences of the z character.

| String | Z-Encoded String |

|---|---|

foo |

foo |

z |

zz |

Z |

ZZ |

. |

. |

() |

Z0T |

(,) |

Z2T |

(,,) |

Z3T |

_ |

zu |

( |

ZL |

) |

ZR |

: |

ZC |

# |

zh |

. |

zi |

(#,#) |

Z2H |

(->) |

ZLzmzgZR |

In this way we don't have to generate unique unidentifiable names for character rich names and can simply have a straightforward way to translate them into something unique but identifiable.

So for some example names from GHC generated code:

| Z-Encoded String | Decoded String |

|---|---|

ZCMain_main_closure |

:Main_main_closure |

base_GHCziBase_map_closure |

base_GHC.Base_map_closure |

base_GHCziInt_I32zh_con_info |

base_GHC.Int_I32#_con_info |

ghczmprim_GHCziTuple_Z3T_con_info |

ghc-prim_GHC.Tuple_(,,)_con_in |

ghczmprim_GHCziTypes_ZC_con_info |

ghc-prim_GHC.Types_:_con_info |

Cmm

Cmm is GHC's complex internal intermediate representation that maps directly onto the generated code for the compiler target. Cmm code code generated from Haskell is CPS-converted, all functions never return a value, they simply call the next frame in the continuation stack. All evaluation of functions proceed by indirectly jumping to a code object with it's arguments placed on the stack by the caller.

This is drastically different than C's evaluation model, where are placed on the stack and a function yields a value to the stack after it returns.

There are several common suffixes you'll see used in all closures and function names:

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

0 |

No argument |

p |

Garage Collected Pointer |

n |

Word-sized non-pointer |

l |

64-bit non-pointer (long) |

v |

Void |

f |

Float |

d |

Double |

v16 |

16-byte vector |

v32 |

32-byte vector |

v64 |

64-byte vector |

Cmm Registers

There are 10 registers that described in the machine model. Sp is the pointer to top of the stack, SpLim is the pointer to last element in the stack. Hp is the heap pointer, used for allocation and garbage collection with HpLim the current heap limit.

The R1 register always holds the active closure, and subsequent registers are arguments passed in registers. Functions with more than 10 values spill into memory.

- Sp

- SpLim

- Hp

- HpLim

- HpAlloc

- R1

- R2

- R3

- R4

- R5

- R6

- R7

- R8

- R9

- R10

Examples

To understand Cmm it is useful to look at the code generated by the equivalent Haskell and slowly understand the equivalence and mechanical translation maps one to the other.

There are generally two parts to every Cmm definition, the info table and

the entry code. The info table maps directly StgInfoTable struct and

contains various fields related to the type of the closure, it's payload, and

references. The code objects are basic blocks of generated code that correspond

to the logic of the Haskell function/constructor.

For the simplest example consider a constant static constructor. Simply a function which yields the Unit value. In this case the function is simply a constructor with no payload, and is statically allocated.

Haskell:

unit = ()

Cmm:

[section "data" {

unit_closure:

const ()_static_info;

}]

Consider a static constructor with an argument.

Haskell:

con :: Maybe ()

con = Just ()

Cmm:

[section "data" {

con_closure:

const Just_static_info;

const ()_closure+1;

const 1;

}]

Consider a literal constant. This is a static value.

Haskell:

lit :: Int

lit = 1

Cmm:

[section "data" {

lit_closure:

const I#_static_info;

const 1;

}]

Consider the identity function.

Haskell:

id x = x

Cmm:

[section "data" {

id_closure:

const id_info;

},

id_info()

{ label: id_info

rep:HeapRep static { Fun {arity: 1 fun_type: ArgSpec 5} }

}

ch1:

R1 = R2;

jump stg_ap_0_fast; // [R1]

}]

Consider the constant function.

Haskell:

constant x y = x

Cmm:

[section "data" {

constant_closure:

const constant_info;

},

constant_info()

{ label: constant_info

rep:HeapRep static { Fun {arity: 2 fun_type: ArgSpec 12} }

}

cgT:

R1 = R2;

jump stg_ap_0_fast; // [R1]

}]

Consider a function where application of a function ( of unknown arity ) occurs.

Haskell:

compose f g x = f (g x)

Cmm:

[section "data" {

compose_closure:

const compose_info;

},

compose_info()

{ label: compose_info

rep:HeapRep static { Fun {arity: 3 fun_type: ArgSpec 20} }

}

ch9:

Hp = Hp + 32;

if (Hp > HpLim) goto chd;

I64[Hp - 24] = stg_ap_2_upd_info;

I64[Hp - 8] = R3;

I64[Hp + 0] = R4;

R1 = R2;

R2 = Hp - 24;

jump stg_ap_p_fast; // [R1, R2]

che:

R1 = compose_closure;

jump stg_gc_fun; // [R1, R4, R3, R2]

chd:

HpAlloc = 32;

goto che;

}]

Consider a function which branches using pattern matching:

Haskell:

match :: Either a a -> a

match x = case x of

Left a -> a

Right b -> b

Cmm:

[section "data" {

match_closure:

const match_info;

},

sio_ret()

{ label: sio_info

rep:StackRep []

}

ciL:

_ciM::I64 = R1 & 7;

if (_ciM::I64 >= 2) goto ciN;

R1 = I64[R1 + 7];

Sp = Sp + 8;

jump stg_ap_0_fast; // [R1]

ciN:

R1 = I64[R1 + 6];

Sp = Sp + 8;

jump stg_ap_0_fast; // [R1]

},

match_info()

{ label: match_info

rep:HeapRep static { Fun {arity: 1 fun_type: ArgSpec 5} }

}

ciP:

if (Sp - 8 < SpLim) goto ciR;

R1 = R2;

I64[Sp - 8] = sio_info;

Sp = Sp - 8;

if (R1 & 7 != 0) goto ciU;

jump I64[R1]; // [R1]

ciR:

R1 = match_closure;

jump stg_gc_fun; // [R1, R2]

ciU: jump sio_info; // [R1]

}]

Macros

Cmm itself uses many macros to stand for various constructs, many of which are defined in an external C header file. A short reference for the common types:

| Cmm | Description |

|---|---|

C_ |

char |

D_ |

double |

F_ |

float |

W_ |

word |

P_ |

garbage collected pointer |

I_ |

int |

L_ |

long |

FN_ |

function pointer (no arguments) |

EF_ |

extern function pointer |

I8 |

8-bit integer |

I16 |

16-bit integer |

I32 |

32-bit integer |

I64 |

64-bit integer |

Many of the predefined closures (stg_ap_p_fast, etc) are themselves

mechanically generated and more or less share the same form ( a giant switch

statement on closure type, update frame, stack adjustment). Inside of GHC is a

file named GenApply.hs that generates most of these functions. See the Gist

link in the reading section for the current source file that GHC generates. For

example the output for stg_ap_p_fast.

stg_ap_p_fast

{ W_ info;

W_ arity;

if (GETTAG(R1)==1) {

Sp_adj(0);

jump %GET_ENTRY(R1-1) [R1,R2];

}

if (Sp - WDS(2) < SpLim) {

Sp_adj(-2);

W_[Sp+WDS(1)] = R2;

Sp(0) = stg_ap_p_info;

jump __stg_gc_enter_1 [R1];

}

R1 = UNTAG(R1);

info = %GET_STD_INFO(R1);

switch [INVALID_OBJECT .. N_CLOSURE_TYPES] (TO_W_(%INFO_TYPE(info))) {

case FUN,

FUN_1_0,

FUN_0_1,

FUN_2_0,

FUN_1_1,

FUN_0_2,

FUN_STATIC: {

arity = TO_W_(StgFunInfoExtra_arity(%GET_FUN_INFO(R1)));

ASSERT(arity > 0);

if (arity == 1) {

Sp_adj(0);

R1 = R1 + 1;

jump %GET_ENTRY(UNTAG(R1)) [R1,R2];

} else {

Sp_adj(-2);

W_[Sp+WDS(1)] = R2;

if (arity < 8) {

R1 = R1 + arity;

}

BUILD_PAP(1,1,stg_ap_p_info,FUN);

}

}

default: {

Sp_adj(-2);

W_[Sp+WDS(1)] = R2;

jump RET_LBL(stg_ap_p) [];

}

}

}

Handwritten Cmm can be included in a module manually by first compiling it through GHC into an object and then using a special FFI invocation.

#include "Cmm.h"

factorial {

entry:

W_ n ;

W_ acc;

n = R1 ;

acc = n ;

n = n - 1 ;

for:

if (n <= 0 ) {

RET_N(acc);

} else {

acc = acc * n ;

n = n - 1 ;

goto for ;

}

RET_N(0);

}

-- ghc -c factorial.cmm -o factorial.o

-- ghc factorial.o Example.hs -o Example

{-# LANGUAGE MagicHash #-}

{-# LANGUAGE UnliftedFFITypes #-}

{-# LANGUAGE GHCForeignImportPrim #-}

{-# LANGUAGE ForeignFunctionInterface #-}

module Main where

import GHC.Prim

import GHC.Word

foreign import prim "factorial" factorial_cmm :: Word# -> Word#

factorial :: Word64 -> Word64

factorial (W64# n) = W64# (factorial_cmm n)

main :: IO ()

main = print (factorial 5)

See:

Cmm Runtime:

- Apply.cmm

- StgStdThunks.cmm

- StgMiscClosures.cmm

- PrimOps.cmm

- Updates.cmm

- Precompiled Closures ( Autogenerated Output )

最適化ハック

Tables Next to Code

GHC will place the info table for a toplevel closure directly next to the entry-code for the objects in memory such that the fields from the info table can be accessed by pointer arithmetic on the function pointer to the code itself. Not performing this optimization would involve chasing through one more pointer to get to the info table. Given how often info-tables are accessed using the tables-next-to-code optimization results in a tractable speedup.

Pointer Tagging

Depending on the type of the closure involved, GHC will utilize the last few bits in a pointer to the closure to store information that can be read off from the bits of pointer itself before jumping into or access the info tables. For thunks this can be information like whether it is evaluated to WHNF or not, for constructors it contains the constructor tag (if it fits) to avoid an info table lookup.

Depending on the architecture the tag bits are either the last 2 or 3 bits of a pointer.

// 32 bit arch

TAG_BITS = 2

// 64-bit arch

TAG_BITS = 3

These occur in Cmm most frequently via the following macro definitions:

#define TAG_MASK ((1 << TAG_BITS) - 1)

#define UNTAG(p) (p & ~TAG_MASK)

#define GETTAG(p) (p & TAG_MASK)

So for instance in many of the precompiled functions, there will be a test for

whether the active closure R1 is already evaluated.

if (GETTAG(R1)==1) {

Sp_adj(0);

jump %GET_ENTRY(R1-1) [R1,R2];

}